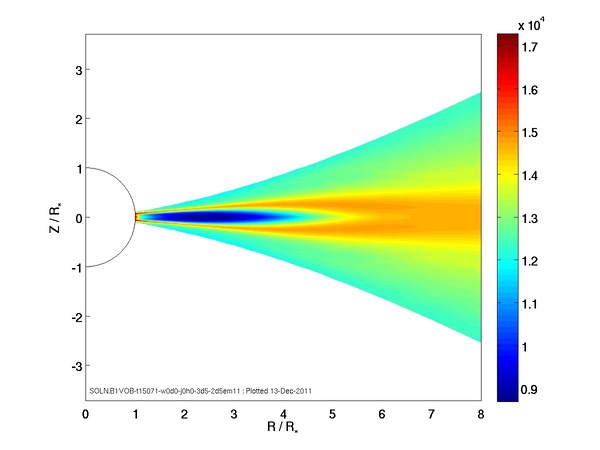

This picture shows the temperature structure of a typical Be star disk. The central star is shown in outline only for reference. The colour bar to the right now represents gas temperature, and colours range from dark blue, for a low of 9,000 degrees, to dark red, for a high for 17,000 degrees,. The temperature of the central star is about 23,000 degrees and is not colour-coded in this image. The most prominent feature of this image is the very cool zone, around 9,000 degrees, in the equatorial plane of the disk and quite close to the star. While it seems odd that the coolest temperatures would be so close to the star, this cool region is a reflection of the disk density shown in the previous figure. Where the density is high and all lines of sight back to the star must pass through regions of high density, little light from the central star can penetrate. But it is this starlight that provides the energy to the disk, heating it. As you move farther away (and to the right in the figure), the gas density drops and some lines of sight back to the star now pass through the relatively less dense upper regions of the disk. This means that lots of starlight can now reach these regions, heating them up. An important point to understand about this figure and the previous one (showing the disk density) is that one does not "see" either temperature or density. Nevertheless, gas of a given density and temperature produces light that we can see. Modelling how this light is emitted by the gas and what happens to it as it travels to us is how an actual image of the star+disk system, like the first slide in this series, can be produced.